Printable Constitution And Amendments

Transcript of 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Civil Rights (1868). AMENDMENT XIV. All persons born or naturalized in the United States,.

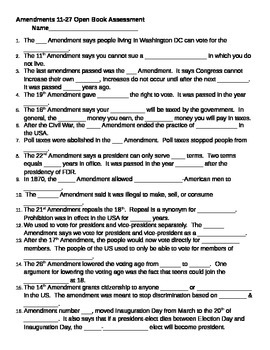

Amendments Showing top 8 worksheets in the category - Amendments. Some of the worksheets displayed are Teachers answer copy, Amendments work, Lesson plan bill of rights and other amendments, Bill of rights and other amendments lesson answer key, 13th 14th 15th amendments, The constitution work virginia plan the, Work understanding the constitution, Bill of rights work. Once you find your worksheet, click on pop-out icon or print icon to worksheet to print or download. Worksheet will open in a new window. You can & download or print using the browser document reader options.

. Article Five of the describes the process whereby the Constitution, the nation's frame of government, may be altered. Under Article V, the process to alter the Constitution consists of proposing an or amendments, and subsequent. Amendments may be proposed either by the with a two-thirds in both the and the or by a called for by two-thirds of the. To become part of the Constitution, an amendment must be ratified by either—as determined by Congress—the legislatures of three-quarters of the or in three-quarters of the states.

The vote of each state (to either ratify or reject a proposed amendment) carries, regardless of a state's population or length of time in the Union. Article V is silent regarding deadlines for the ratification of proposed amendments, but most amendments proposed since 1917 have included a deadline for ratification. Legal scholars generally agree that the amending process of Article V can itself be amended by the procedures laid out in Article V, but there is some disagreement over whether Article V is the exclusive means of amending the Constitution. In addition to defining the procedures for altering the Constitution, Article V also three clauses in from ordinary amendment by attaching stipulations. Regarding two of the clauses—one concerning importation of and the other apportionment of —the prohibition on amendment was absolute but of, expiring in 1808; the third was without an expiration date but less absolute: 'no state, without its consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate.' Scholars disagree as to whether this shielded clause can itself be amended by the procedures laid out in Article V. Constitutional amendment process to the United States Constitution have been approved by the Congress and sent to the states for ratification.

Twenty-seven of these amendments have been ratified and are now part of the Constitution. The first ten amendments were adopted and ratified simultaneously and are known collectively as the. Six amendments adopted by Congress and sent to the states have not been ratified by the required number of states and are not part of the Constitution.

Four of these amendments are still technically open and pending, one is closed and has failed by its own terms, and one is closed and has failed by the terms of the resolution proposing it. All totaled, approximately 11,539 measures to amend the Constitution have been proposed in Congress since 1789 (through December 16, 2014). Proposing amendments Article V provides two methods for amending the nation's frame of government.

The first method authorizes Congress, 'whenever two-thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary' (a two-thirds of those members present—assuming that a exists at the time that the vote is cast—and not necessarily a two-thirds vote of the entire membership elected and serving in the two houses of Congress), to propose Constitutional amendments. The second method requires Congress, 'on the application of the legislatures of two-thirds of the several states' (presently 34), to 'call a convention for proposing amendments'. This duality in Article V is the result of compromises made during the between two groups, one maintaining that the national legislature should have no role in the constitutional amendment process, and another contending that proposals to amend the constitution should originate in the national legislature and their ratification should be decided by state legislatures or state conventions. Regarding the consensus amendment process crafted during the convention, (writing in The ) declared: It guards equally against that extreme facility which would render the Constitution too mutable; and that extreme difficulty which might perpetuate its discovered faults. It moreover equally enables the General and the State Governments to originate the amendment of errors, as they may be pointed out by the experience on one side, or on the other.

Each time the Article V process has been initiated since 1789, the first method for crafting and proposing amendments has been used. All 33 amendments submitted to the states for ratification originated in the Congress. The second method, the convention option, a political tool which (writing in The ) argued would enable state legislatures to 'erect barriers against the encroachments of the national authority', has yet to be invoked. Resolution proposing the When the considered a series of, it was suggested that the two houses first adopt a resolution indicating that they deemed amendments necessary. This procedure was not used. Instead, both the House and the Senate proceeded directly to consideration of a, thereby implying that both bodies deemed amendments to be necessary. Also, when initially proposed by, the amendments were designed to be interwoven into the relevant sections of the original document.

Instead, they were approved by Congress and sent to the states for ratification as supplemental additions appended to it. Both these have been followed ever since. Once approved by Congress, the joint resolution proposing a constitutional amendment does not require approval before it goes out to the states. While Article I provides that all must, before becoming Law, be presented to the President for his or her or, Article V provides no such requirement for constitutional amendments approved by Congress, or by a federal convention. Thus the president has no official function in the process.

In (1798), the affirmed that it is not necessary to place constitutional amendments before the President for approval or veto. Three times in the 20th century, concerted efforts were undertaken by proponents of particular amendments to secure the number of applications necessary to summon an Article V Convention.

These included conventions to consider amendments to (1) provide for popular election of U.S. Senators; (2) permit the states to include factors other than equality of population in drawing state legislative boundaries; and (3) to propose an requiring the U.S.

Budget to be balanced under most circumstances. The campaign for a popularly elected Senate is frequently credited with 'prodding' the Senate to join the House of Representatives in proposing what became the to the states in 1912, while the latter two campaigns came very close to meeting the two-thirds threshold in the 1960s and 1980s, respectively. Certificate of ratification of the; with this ratification, the amendment became valid as a part of the Constitution After being officially proposed, either by Congress or a national convention of the states, a constitutional amendment must then be ratified by three-fourths of the states. Congress is authorized to choose whether a proposed amendment is sent to the state legislatures or to state ratifying conventions for ratification. Amendments ratified by the states under either procedure are indistinguishable and have equal validity as part of the Constitution.

Of the 33 amendments submitted to the states for ratification, the state convention method has been used for only one, the. In (1931), the Supreme Court affirmed the authority of Congress to decide which mode of ratification will be used for each individual constitutional amendment. The Court had earlier, in (1920), upheld the 's ratification of the —which Congress had sent to the state legislatures for ratification—after Ohio voters successfully vetoed that approval through a, ruling that a provision in the reserving to the state's voters the right to challenge and overturn its legislature's ratification of federal constitutional amendments was unconstitutional.

An amendment becomes an operative part of the Constitution when it is ratified by the necessary number of states, rather than on the later date when its ratification is certified. No further action by Congress or anyone is required. On three occasions, Congress has, after being informed that an amendment has reached the ratification threshold, adopted a resolution declaring the process successfully completed.

Such actions, while perhaps important for political reasons, are, constitutionally speaking, unnecessary. Presently, the is charged with responsibility for administering the ratification process under the provisions of.

The Archivist officially notifies the states, by a letter to each state's, that an amendment has been proposed. Each Governor then formally submits the amendment to their state's legislature (or ratifying convention). When a state ratifies a proposed amendment, it sends the Archivist an original or certified copy of the state's action. Upon receiving the necessary number of state ratifications, it is the duty of the Archivist to issue a certificate a particular amendment duly ratified and part of the Constitution. The amendment and its certificate of ratification are then published in the. This serves as official notice to Congress and to the nation that the ratification process has been successfully completed. Ratification deadline and extension The Constitution is silent on the issue of whether or not Congress may limit the length of time that the states have to ratify constitutional amendments sent for their consideration.

It is also silent on the issue of whether or not Congress, once it has sent an amendment that includes a ratification deadline to the states for their consideration, can extend that deadline. Deadlines The practice of limiting the time available to the states to ratify proposed amendments began in 1917 with the.

All amendments proposed since then, with the exception of the Nineteenth Amendment and the (still pending), have included a deadline, either in the body of the proposed amendment, or in the joint resolution transmitting it to the states. The ratification deadline 'clock' begins running on the day final action is completed in Congress. An amendment may be ratified at any time after final congressional action, even if the states have not yet been officially notified. In (1921), the Supreme Court upheld Congress's power to prescribe time limitations for state ratifications and intimated that clearly out of date proposals were no longer open for ratification.

Granting that it found nothing express in Article V relating to time constraints, the Court yet allowed that it found intimated in the amending process a 'strongly suggestive' argument that proposed amendments are not open to ratification for all time or by States acting at widely separate times. The court subsequently, in (1939), modified its opinion considerably. In that case, related to the proposed Child Labor Amendment, it held that the question of timeliness of ratification is a political and non-justiciable one, leaving the issue to Congress's discretion. It would appear that the length of time elapsing between proposal and ratification is irrelevant to the validity of the amendment. Based upon this precedent, the Archivist of the United States proclaimed the as having been ratified when it surpassed the 'three fourths of the several states' plateau for becoming a part of the Constitution. Declared ratified on May 7, 1992, it had been submitted to the states for ratification—without a ratification deadline—on September 25, 1789, an unprecedented time period of 202 years, 7 months and 12 days. Extensions Whether once it has prescribed a ratification period Congress may extend the period without necessitating action by already-ratified States embroiled Congress, the states, and the courts in argument with respect to the proposed Equal Rights Amendment (Sent to the states on March 22, 1972 with a seven-year ratification time limit attached).

In 1978 Congress, by simple vote in both houses, extended the original deadline by 3 years, 3 months and 8 days (through June 30, 1982). The amendment's proponents argued that the fixing of a time limit and the extending of it were powers committed exclusively to Congress under the political question doctrine and that in any event Congress had power to extend. It was argued that inasmuch as the fixing of a reasonable time was within Congress' power and that Congress could fix the time either in advance or at some later point, based upon its evaluation of the social and other bases of the necessities of the amendment, Congress did not do violence to the Constitution when, once having fixed the time, it subsequently extended the time. Proponents recognized that if the time limit was fixed in the text of the amendment Congress could not alter it because the time limit as well as the substantive provisions of the proposal had been subject to ratification by a number of States, making it unalterable by Congress except through the amending process again. Opponents argued that Congress, having by a two-thirds vote sent the amendment and its authorizing resolution to the states, had put the matter beyond changing by passage of a simple resolution, that states had either acted upon the entire package or at least that they had or could have acted affirmatively upon the promise of Congress that if the amendment had not been ratified within the prescribed period it would expire and their assent would not be compelled for longer than they had intended.

In 1981, the, however, found that Congress did not have the authority to extend the deadline, even when only contained within the proposing joint resolution's resolving clause. The Supreme Court had decided to take up the case, bypassing the Court of Appeals, but before they could hear the case, the extended period granted by Congress had been exhausted without the necessary number of states, thus rendering the case.

Entrenchment clauses. See also: Article V contains two defunct provisions designed to certain clauses in from being amended. The, which prevented Congress from passing any law that would restrict the importation of prior to 1808, and the, a declaration that must be apportioned according to state populations, were explicitly shielded from Constitutional amendment prior to 1808. Article V also contains a clause that shields the which provides for equal representation of the states in the, from being amended. Unlike the other two shielding provisions, this provision does not contain an expiration date and remains in effect. The provision does allow for a state to lose equal representation in the Senate if that state consents to the loss of equal representation. Amending Article V Article V lays out the procedures for amending the Constitution, but does not explicitly state whether those procedures apply to Article V itself.

According to law professor George Mader, there have been numerous proposals to amend the Constitution's amending procedures, and 'it is generally accepted that constitutional amending provisions can be used to amend themselves.' Some scholars contend that even the provision protecting equal suffrage in the Senate from amendment is itself amendable.

Mader holds that the shielding provision can be amended because it is not 'self-entrenched,' meaning that it does not contain a provision preventing its own amendment. Thus, under Mader's argument, a two-step amendment process could repeal the provision that prevents the equal suffrage provision from being amended, and then repeal the equal suffrage provision itself. Mader contrasts the provision preventing the amendment of equal suffrage with the proposed, a package of unratified constitutional amendments that did contain a self-entrenching provision that would have totally closed off any possibility of future amendments affecting certain constitutional provisions. Law professor Richard Albert also holds that the equal suffrage provision could be amended through a 'double amendment' process, contrasting the U.S.

Constitution with other constitutions that explicitly protect certain provisions from ever being amended and are themselves protected from being amended. Another legal scholar, argues that the equal suffrage provision could be amended through a two-step process, but describes that process as a 'sly scheme.' Some other legal scholars, including Thomas A. Baker and Douglas Linder, have rejected the notion that the equal suffrage provision could ever be amended without the consent of each state.

Exclusive means for amending the Constitution According to constitutional theorist and scholar, some commentators have seriously questioned whether Article V is the exclusive means of amending the Constitution, or whether there are routes to amendment, including some routes in which the Constitution could be unconsciously or unwittingly amended in a period of sustained political activity on the part of a mobilized national constituency. For example, rejects the notion that Article V excludes other modes of constitutional change, arguing instead that the procedure provided for in Article V is simply the exclusive method the government may use to amend the Constitution. He asserts that Article V nowhere prevents the People themselves, acting apart from ordinary Government, from exercising their legal right to alter or abolish Government via the proper legal procedures. Argues that the Constitution can be amended by something he calls a 'structural amendment' whereby the people alter their Constitutional order via succeeding elections. Similarly, believes that Constitutional amendments have been made outside of Article V and as such it is not exclusive.

Other scholars disagree with Amar, Ackerman, and Levinson. Some argue that the Constitution itself provides no mechanism for the American people to adopt constitutional amendments independently of Article V. Darren Patrick Guerra has argued that Article V is a vital part of the American Constitutional tradition and he defends Article V against modern critiques that Article V is either too difficult, too undemocratic, or too formal. Instead he argues that Article V provides a clear and stable way of amending the document that is explicit, authentic, and the exclusive means of amendment; it promotes wisdom and justice through enhancing deliberation and prudence; and its process complements federalism and separation of powers that are key features of the Constitution.

He argues that Article V remains the most clear and powerful way to register the sovereign desires of the American public with regard to alterations of their fundamental law. In the end, Article V is an essential bulwark to maintaining a written Constitution that secures the rights of the people against both elites and themselves. In, President said: If in the opinion of the People the distribution or modification of the Constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed. The precedent must always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any partial or transient benefit which the use can at any time yield. This statement by Washington has become controversial, and scholars disagree about whether it still describes the proper constitutional order in the United States. Scholars who dismiss Washington's position often argue that the Constitution itself was adopted without following the procedures in the, while Constitutional disagrees, saying the Convention was a product of the States', and the amendment in adoption process was legal, having received the unanimous assent of the States' legislatures.

See also. Notes.

On March 2, 1861 the gave final approval to proposed constitutional amendment designed to shield 'domestic institutions' (which at the time included ) from the constitutional amendment process and from abolition or interference by Congress. The following day, on his last full day in office, President, took the unprecedented step of signing it. Submitted to the state legislatures for ratification without a time limit for ratification attached, the proposal, commonly known as the, is still technically pending before the states. On January 31, 1865, the gave final approval to what would become the, which abolished slavery and, except. The following day, the amendment was presented to the President pursuant to the constitution’s, and signed.

On February 7, Congress passed a resolution affirming that the Presidential signature was unnecessary. 1868 regarding the, 1870 regarding the, and 1992 regarding the. In recent history, the signing of the certificate of ratification has become a ceremonial function attended by various dignitaries. President signed the certifications for the and as a witness.

When the, certified the adoption of the on July 5, 1971, President along with Julianne Jones, Joseph W. Loyd Jr., and Paul Larimer of the 'Young Americans in Concert' signed as witnesses. On May 18, 1992, the Archivist of the United States, certified that the had been ratified, and the Director of the, Martha Girard, signed the certification as a witness. Congress incorporated the ratification deadline for the, and amendments into the body of the amendment, so these amendments' deadlines are now part of the Constitution. The failed also contained a ratification deadline clause.

Congress inserted the ratification deadline for the, and amendments into the joint resolutions transmitting them to the state legislatures in order to avoid including extraneous language in the Constitution. This practice was also followed for the failed. References. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

Wines, Michael (August 22, 2016). Retrieved August 24, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2014. Statistics & Lists.

United States Senate. ^ Neale, Thomas H. (April 11, 2014). Retrieved November 17, 2015. Rogers, James Kenneth (Summer 2007). 30 (3): 1005–1022. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

^ England, Trent; Spalding, Matthew. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved December 5, 2018. Dranias, Nick (December 6, 2013).

Constitution Daily. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: National Constitution Center. Retrieved May 30, 2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

Tsesis, Alexander (2004). The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York: New York University Press. Chicago: Callaghan & Company. Rossum, Ralph A. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Retrieved October 23, 2015. ^ (December 1983). Harvard Law Review. Retrieved May 30, 2018. Columbus Ohio: Ohio History Connection (formerly the Ohio Historical Society). Retrieved May 30, 2018.

Neale, Thomas H. (May 9, 2013). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

Printable Us Constitution And Amendments

^ Huckabee, David C. (September 30, 1997).

Washington D.C.:, The. Nixon, Richard (July 5, 1971). Online by Gerhard Peters and John T.

Woolley, The American Presidency Project. Retrieved May 30, 2018. Vile, John R.

(Second ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc. Retrieved November 22, 2015. Freeman, 529 F.

Certiorari before judgment granted, NOW v. Idaho, 455 U.S. Judgments of the District Court of Idaho vacated; cases remanded with instructions to dismiss as moot. Idaho, 459 U.S.

Mader, George (Summer 2016). Marquette Law Review. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

Mader (2016), p. 866–867.

Mader (2016), pp. 885–886. Albert, Richard (2015). International Journal of Constitutional Law: 8–9.

Baker, Lynn A.; Dinkin, Samuel H. Journal of Law & Politics. 13 (21): 68–72. Sager, Lawrence (2006). Yale University Press. Bowman, Scott J.

Fordham Law Review. 72 (4): 1026–27. Retrieved August 28, 2016. Ackerman, Bruce A. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. – via Google Books. Levinson, Sanford (1995).

Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. – via Google Books.

Manheim, Karl and Howard, Edward., Loyola Los Angeles Law Review, p. Guerra, Darren Patrick (2013). Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

– via Google Books. Washington, George. Strauss, David. 114 Harvard Law Review 1457 (2001). Fritz, Christian., Rutgers Law Journal, p.

Farris, Michael. Convention of States Project. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

External links.